In April 2001, Madonna released her hit single “What it Feels Like for a Girl” where she captures with a poetic vulnerability that not all girls live idyllic childhoods:

Hurt that’s not supposed to show

And tears that fall when no one knows

When you’re trying hard to be your best

Could you be a little less?

(What it feels like for a girl, n.d., para. 7)

Museum curator and historian Kathleen Franz (2021) and her colleagues argue that “popular notions of girlhood privilege some girlhoods while erasing others” (p. 147). As such, “[n]ot every girl [has] the ideal girlhood; some [don’t] have a girlhood at all” (Franz et al., 2021, p. 146). Crystal Webster, a historian of African American women and children, shares in a Washington Post article that girls marginalized by race or class often “face disbarment from ideas of childhood and girlhood” (Webster, 2020, para. 13). Through my graduate studies research, I have revealed that there is another marginalized group of girls who are also systematically robbed of their girlhoods – foster girls.

What is Girlhood?

Before we can determine if something is lost, we must first define what that something is. The Encyclopedia of Motherhood, edited by world-renowned maternal theory scholar Dr. Andrea O’Reilly, suggests that girlhood today “serves as an umbrella term encompassing the totality of female experience up to childbirth, substituting among others, the concept of womanhood” (“Girlhood and Motherhood,” 2010, p. 455). As a constructed identity it has come to embody characteristics such as politeness, deference to authority, sexual chastity (as well as sexuality and sexual attractiveness), consumerism and more recently, empowerment (“Girlhood and Motherhood,” 2010, p. 455).

Monica Swindle (2011), a professor of gender studies at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, goes beyond “the way that girl has been understood previously, as a discursively constructed subject identity” (p. 7) and takes a page out of Madonna’s songbook when she concludes “girl is something one can now feel as well as be or feel even if one isn’t” (p. 15). Yet she also clearly notes that this feeling of girl is a feeling for the privileged. She provides a lengthy account of the many, many girls in this world who are excluded and thus, invisible:

“Young female bodies that are fat. Starving. Scarred by war. Cut. Torn by abuse of assault. Non-white bodies. Poor bodies. Non-Western bodies. Differently-abled bodies. Transgender bodies. Bodies sadly not materialized by the pleasure and power of girl but by misogyny, by hate.” (Swindle, 2011, p. 15)

As I share below, foster girls in Canada are undeniably excluded from being and feeling girl.

Three Foster Girls Tell Their Stories

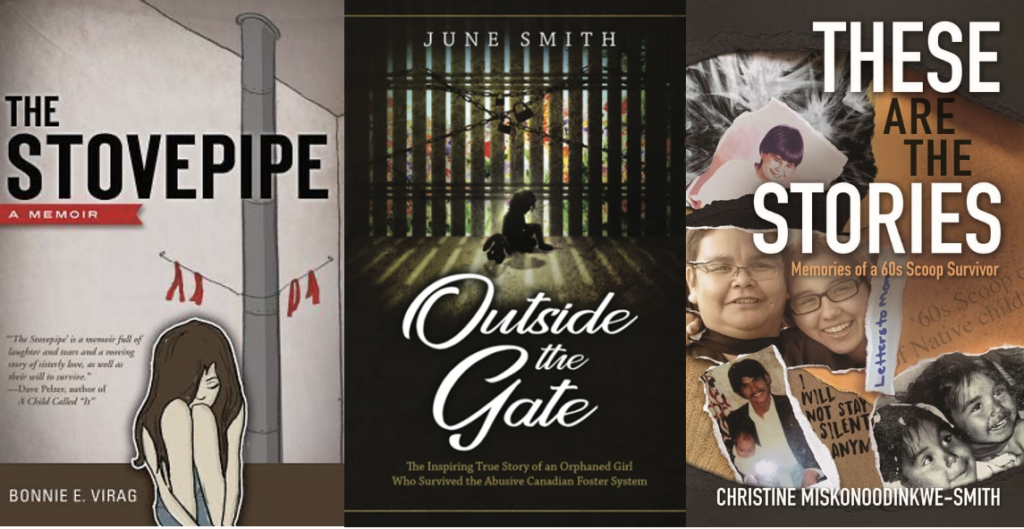

The three memoirs I studied and analyzed were The Stovepipe by Bonnie E. Virag (2011), Outside the Gate: The Inspiring True Story of an Orphaned Girl Who Survived the Abusive Canadian Foster System by June Smith (2022), and These Are the Stories: Memories of a 60s Scoop Survivor by Christine Miskonoodinkwe Smith (2021). All three authors are former foster girls raised in Ontario, Canada during the 1940s to 1960s.

Girlhood Gone On Three Levels – Abuse, Impoverishment & Race

Using Swindle’s (2011) list of the type of girls that get excluded from the luxury of girlhood, it is clear Virag (2011), Smith (2022), and Miskonoodinkwe Smith (2021) – victims of abuse at the hands of their foster parents – are rendered invisible. The three former foster girls share:

“Mr. Bender grabbed my sisters one by one – first Betty, then Joan, and then Jean. Holding their arms with one hand and swinging the thick stick with other – showing no mercy … Once he had broken them down and they cried out in pain, he let them go and reached for me.” (Virag, 2011, p. 312)

“She proceeded to beat me with the mop she was wielding … Full of pain, I managed to stand up. My legs buckled down under me.” (Smith, 2022, p. 96)

“Punishment came in the form of a few good swats on my behind with a flyswatter, or a strike across the face with an open palm … Though I never knew what punishment may come, the worst was always being locked up.” (Miskonoodinkwe Smith, 2021, p. 9)

As the memoirs reveal, these young girls are also impoverished. UK scholars Samantha Holland and Julie Harpin (2013) point out in their study on girly-girls and Tomboys that “Working-class girls cannot necessarily afford the trappings of the girly-girl” (Holland & Harpin, 2013, p. 299). In her critical analysis of Angela McRobbie and Jenny Garber’s trailblazing Theory of Bedroom Culture, Mary Celeste Kearney (Associate Professor & Researcher in the University of Notre Dame’s Department of Film, Television, and Theatre) argues, “in contrast to poor youth, wealthy adolescent girls have traditionally had their own bedrooms and have used such spaces for both individual and collective recreational activities, including reading, handicrafts, musical performance, diary writing and tea parties” (Cromely, 1992; Hunter, 2022, as cited in Kearney, 2007, p. 129). What kind of girl bedroom culture did our three foster girls experience?

“In the winter months it was so frigid in these unfinished rooms that we had to sleep with our winter coats on top of our flannel nightgowns and chenille robes … Having no games, puzzles, or toys of any kind, we idled away our time reading or doing homework.” (Virag, 2011, p. 159)

“Lucie [foster sister] took me upstairs to our room … I would be sleeping on the top bunk in the narrow room, with one small window … There was one dresser, and she opened two empty drawers and indicated I could use them … There was no lamp in the room, and I wondered where I would read.” (Smith, 2022, pp. 81-82)

“My bedroom consisted of a wooden bunk bed, a dresser and a desk and chair that faced a window … My bedroom served as my prison. It had bolts on the door. There was an alarm that would go off shrilly if I even touched the doorknob.” (Miskonoodinkwe Smith, 2021, p. 9)

Lastly, even in the world of foster care there is a social hierarchy and our three foster girls were a far cry from the ideal child that Canadian scholars, Daniella Bendo, Taryn Hepburn, Dale Spencer, and Raven Sinclair (2019) write about in their revealing article about the “Today’s Child” column published in the Toronto Telegram and the Toronto Star in the 1960s to 1980s. They demonstrate unequivocally that “Today’s Child” – whose purpose was to find homes for hard-to-adopt children – believed the ideal child at the top of the hierarchy was a “blonde, white, baby girl, with no siblings” (Bendo et al., 2019, p. 10).

Bonnie Virag (2011) believed her grandmother was part “Mohawk Indian” (p. 10) and as Christine Miskonoodinkwe Smith (2021) shares, “I am a Sixties Scoop survivor, a Bill C-31 status Anishinaabe woman and a daughter of a Saulteaux mother and a Cree father” (p. v). This resulted in Miskonoodinkwe Smith (2021) experiencing racism and isolation:

“Classmates would make fun of me, and it would just make me furious, but I kept the anger inside. That anger turned into more self-harm—cutting myself, overdosing on my medications, anything that would take away the inner pain I was experiencing.” (p. 3)

With 52.2% of foster children in Canada being Indigenous (Statistics Canada, 2016, as cited in Treleaven, 2019) and 40% of the children in the Toronto Children’s Aid Society being Black (Contenta et al, 2014), most foster girls in Canada are excluded from experiencing girlhood.

Resistance is possible, however. As University of Victoria’s Sandrina de Finney (2014) asserts, “Girls negotiate resurgence and resist sustained assaults on Indigenous bodies, lands, and sovereign National through everyday practices of ceremony, hope, creativity, subversion, storytelling, outrage, dream work, political action, critical analysis, and centering community knowledges” (p. 21). Perhaps this should be the new, improved definition of girlhood.

Madonna’s Two Cents

Madonna Louise Veronica Ciccone of Bay City, Michigan (“Madonna,” 2021) burst onto the music scene in 1983 with her self-titled album, Madonna (Murphy, 2023, para. 1) and since then, has reached top ten status on the Billboard Charts 38 times in her 40-year career (Caulfield, 2023). In a 2001 interview the Queen of Pop remarks, “I woke up one day holding the golden ring, and realized that smart, sassy girls who accomplish a lot and have their own cash are independent and really frightening to men” (Madonna, 2001, as cited in Szendry & Morris, 2022, para. 17). Indeed, as the Material Girl shows, the concept of girlhood and being or feeling girl currently can only be accessed by the privileged. We girls need to change that.

References

Bendo, D., Hepburn, T., Spencer, D., & Sinclair, R. (2019). Advertising “happy” children: The settler family, happiness, and the Indigenous child removal system, Children & Society, 1-15. doi:10.1111/chso.12335

Caulfield, K. (2023, August 16). Madonna’s 40 biggest Billboard hits. Billboard.

https://www.billboard.com/lists/madonnas-40-biggest-billboard-hits

Contenta, S., Monsebraaten, L., & Rankin, J. (2014, December 12). Ontario’s most vulnerable children kept in the shadows. Toronto Star.

de Finney, S. (2014). Under the shadow of empire: Indigenous girls’ presencing as decolonizing force. Girlhood studies 7(1), 8–26.

Franz, K., Bercaw, N., Cohen, K., Loza, M., & Vong, S. (2021). Girlhood (It’s complicated) An exhibition: Exploring the politics of girlhood. The Public Historian, 43(1), 138-163.

Girlhood and Motherhood. (2010). In A. O’Reilly (Ed.), Encyclopedia of motherhood (p. 129). Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Holland, S., & Harpin, J. (2015). Who ss the ‘girly’ girl? Tomboys, hyper-femininity and gender. Journal of Gender Studies 24(3), 293–309.

Kearney, M. C. (2007). Productive spaces: Girls’ bedrooms as sites of cultural production. Journal of Children and Media 1(2), 126–41.

Madonna. (2021). Biography. https://www.biography.com/musicians/madonna

Miskonoodinkwe-Smith, C. (2021). These are the stories: Memories of a 60s Scoop survivor. Kegedonce Press.

Murphy, C. (2023, July 27). 40 years of Madonna. Vanity Fair. https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2023/07/40-years-of-madonna

Szendry, M. D. J., & Morris, O. G. (2022, June 24). Life lessons: Four decades of Madonna and Interview. Interview Magazine.

https://www.interviewmagazine.com/music/life-lessons-four-decades-of-madonna-and-interview

Smith, J. (2022). Outside the gate: The inspiring true story of an orphaned girl who survived the abusive Canadian foster system. Westbow Press.

Swindle, M. (2011). Feeling girl, girling feeling: An examination of “girl” as affect. Rhizomes, http://www.rhizomes.net/issue22/swindle.html

Treleaven, S. (2019, November 12). Life after foster care in Canada: Kids who grow up in the system are not expected to do well. That’s a big part of why they don’t. MACLEAN’S. https://www.macleans.ca/society/life-after-foster-care-in-canada/

Virag, B. E. (2011). The stovepipe: A memoir. Langdon Street Press.

Webster, C. L. (2020). The history of Black girls and the field of Black girlhood studies at the forefront of academic scholarship. The American Historian, 38.

What if feels like for a girl. (n.d.) Genius. Retrieved April 12, 2024, from https://genius.com/Madonna-what-it-feels-like-for-a-girl-lyrics

Yes, change is needed.💚