“Do you refuse to laugh at offensive jokes? Have you ever been accused of ruining a dinner by calling out a sexist or racist comment? Are you often told to stop being so ‘woke’?” (Ahmed, 2023, Inside Front Cover). So begins feminist writer and independent scholar Sara Ahmed’s book The Feminist Killjoy Handbook. Indeed, it is to this insightful and brilliant person that I not only owe the name of this blog – Dinner Party Killjoy – but to whom I also owe my sanity. Thanks to Ahmed (2017), I finally understand why I never quite fit in … and why when I exposed a problem, I posed a problem, and thus became a problem (p. 37).

My story of becoming a feminist killjoy begins with music. My father had a wonderful singing voice. On many Saturday afternoons, he would sit alone at the dining room table and sing along with the likes of Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, and Al Jolson. (Yes, that Al Jolson.) As the story goes, my father had opportunity as a teenager to perform in New York state, but his mother wouldn’t hear of it. I wonder now if that’s why he often closed his eyes when he sang. Maybe he was transporting himself to some smoky bar in Buffalo imagining what could have been. On one occasion, my father placed my older sister on this knee and began to serenade her with this old Mills Brothers song:

You’re the end of the rainbow, my pot of gold

You’re daddy’s little girl to have and to hold

A precious gem is what you are

You’re mommy’s bright and shining star.

You’re the spirit of Christmas, my star on the tree

You’re the Easter Bunny to mommy and me

You’re sugar, you’re spice, you’re everything nice

And you’re daddy’s little girl. And you’re daddy’s little girl

(Lyrics.com)

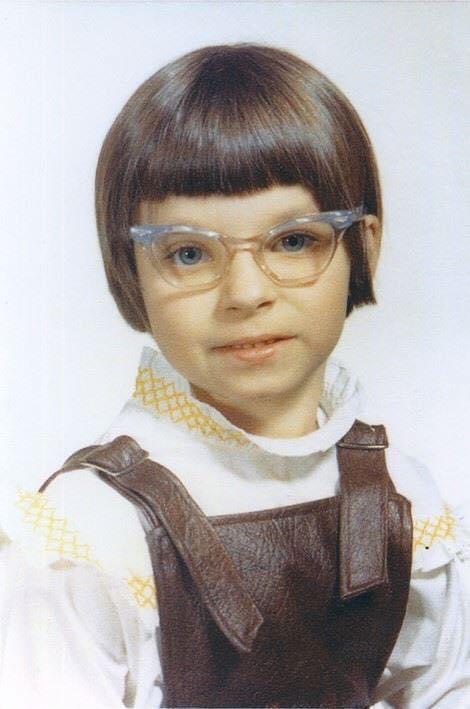

After giving her a gentle squeeze, he beckons me to come over. I, too, nestle into his lap wondering what song he will sing to me. I couldn’t have been more than five or six years old. He begins:

Oh, I don’t want her, you can have her

She’s too fat for me

She’s too fat for me

She’s too fat for me

I don’t want her, you can have her,

She’s too fat for me

She’s too fat

She’s too fat

She’s too fat for me

(Lyrics.com)

I recall running to my bedroom in tears. My mother rushing from the kitchen to see what had happened. My father’s response loud enough for me to hear, “Come on, I was only kidding! It was just a joke!”

Clearly, by not appreciating the joke, I was ruining the fun. As Ahmed (2023) explains: “You become a feminist killjoy when you get in the way of the happiness of others, or when you just get in the way, ruining that dinner, also the atmosphere. You become a feminist killjoy when you are not willing to go along with something, to get along with someone, sitting there quietly, taking it all in. You become a feminist killjoy when you react, speak back, to those with authority, using words like sexism [or racism, classism, ageism, heterosexism, ableism, and sizeism] because that is what you hear. There is so much you are supposed to avoid saying or doing in order not to ruin an occasion. Another dinner ruined, so many dinners ruined” (pp. 1-2).

Do eyes roll wherever you go? Whatever you say? Even if you don’t say anything? Yes. As Ahmed (2017) notes, “It can seem as if eyes roll as an expression of collective exasperation because you are a feminist” (p. 38). A feminist killjoy. But how did you become a feminist? According to Ahmed (2017), it likely started because of an injustice you either experienced or sensed. Moreover, it probably “involved unwanted male attention” (Ahmed, 2017, p. 22). That last line stopped me in my tracks. How about you?

A memory came rushing back to me: I was touring a toy manufacturer for a grade nine school project. The company was a client of my father’s and while he attended a photo shoot, one of the workers showed me around. Deeper and deeper into the warehouse of towering boxes I followed this man. Finding myself trapped in a back corner, the man lunged at me. I can still see his puckered lips searching for my face while his hands gripped my body. I screamed and broke free, running until I arrived back to the photo shoot area. Did I burst into this room of men… important men… businessmen… busy men and share how one of their own had just assaulted me? No, no, no, no, no. This was a CLIENT. So, I waited until I was in the car, in the company parking lot, alone with my father. After I told him what happened, he laughed and put the car in drive.

Indeed, Ahmed (2017) is right when she writes: “[F]eminism is a sensible reaction to the injustices of the world, we might register at first through our own experiences” (p. 21). More importantly, “Feminism helps you to make sense that something is wrong; to recognize a wrong is to realize that you are not in the wrong” (Ahmed, 2017, p. 27). I wasn’t wrong when I was offended by my father’s ‘joke.’ I wasn’t wrong when I realized something was very wrong when capitalism trumped (yes, I use that word deliberately) my safety. I’m not wrong today when I ruin a dinner by calling out a sexist or racist comment. And neither are you.

If you are looking to embrace your inner feminist killjoy, I highly recommend you checkout Sara Ahmed’s Living a Feminist Life and The Feminist Killjoy Handbook. You will feel empowered and emboldened by Ahmed’s (2107) “Killjoy Survival Kit” and “Killjoy Manifesto” in the former. You will also be inspired to embrace and support the feminist killjoys around you. Ahmed (2017) encourages us to give support to the unsupported. To speak out as we wish others had spoken out in support of us. To not leave the feminist killjoy taking a stand, standing alone at the dinner table or the boardroom table. To be a killjoy defender and turn the tables on the offender.

“There can be joy in finding killjoys; there can be joy in killing joy” (Ahmed, 2017, p. 268). There can be joy in ruining dinner parties. So many dinner parties.

References:

Ahmed, S. (2023). The feminist killjoy handbook: The radical potential of getting in the way. Seal Press.

Ahmed, S. (2017). Living a feminist life. Duke University Press.

Daddy’s Little Girl Lyrics. (n.d.). Lyrics.com. Retrieved May 31, 2024, from https://www.lyrics.com/lyric/29305301/The+Mills+Brothers/Daddy%26%23039%3Bs+Little+Girl.

Too Fat Polka (She’s Too Fat for Me) Lyrics. (n.d.). Lyrics.com. Retrieved June 1, 2024, from https://www.lyrics.com/lyric-lf/792271/The+Andrews+Sisters/Too+Fat+Polka+%28She%26%23039%3Bs+Too+Fat+for+Me%29.